NIEMISKYLÄN KORTTELIMALLEJA

BLOCK MODELS OF NIEMISKYLÄ

NIEMISKYLÄN KORTTELIMALLEJA

BLOCK MODELS OF NIEMISKYLÄ

Niemiskylä –visio: mentaalinen esteettömyys

Niemiskylä vision – mental accessibility

Osallistuessamme Helsinki 2050 Visions -kilpailuun vuonna 2007 arkkitehti Pekka Hänninen toi esiin ajatuksen: sen sijaan, että asutusta keskitetään metropolialueella Helsingin niemen tuntumaan, rakentamista voisi suunnata kyliin, joilla on oma keskuksensa ja joihin pääsee nopeilla raideyhteyksillä.

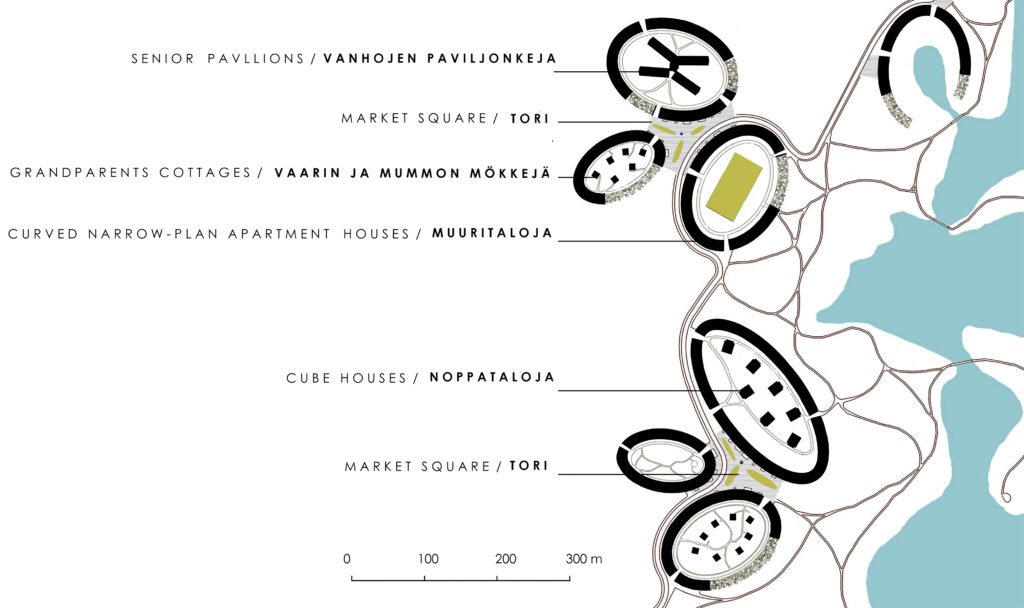

Niemiskylä voisi sijaita minkä tahansa suomalaisen keskisuuren kaupungin kyljessä. Sinne johtaisi sujuva raitiotieyhteys kaupungin asemilta. Auton omistaminen kylän sisällä liikkumiseen ei ole tarpeellista.

Jos Niemiskylä rakennetaan itsenäiseksi taajamaksi, julkiselle liikenteelle pitää rakentaa asemat ja yksityisautojen säilytykselle osoittaa alueet kylän tuntumassa.

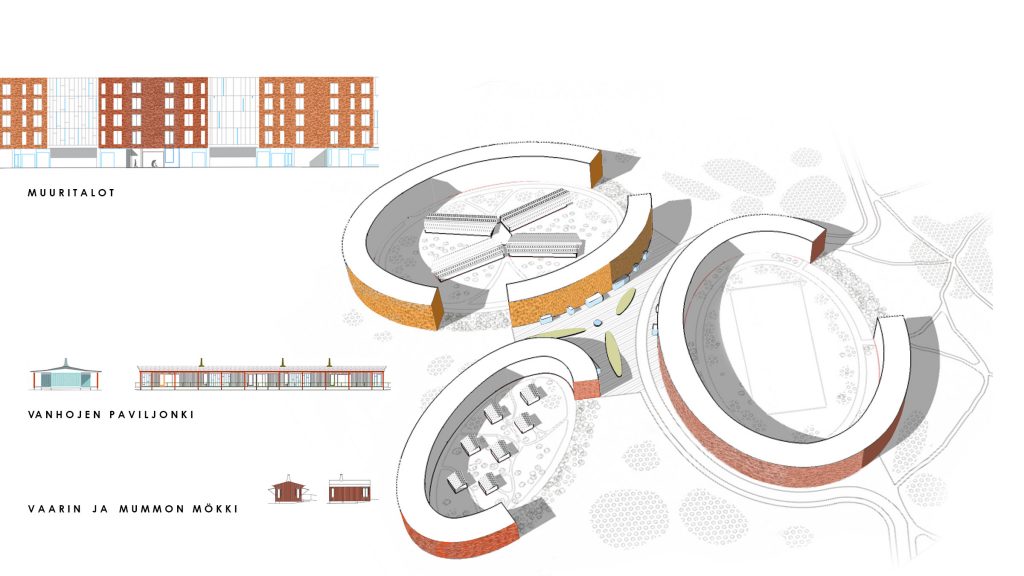

Idea Niemiskylän asuinkortteleista perustuu Hollannista saatuihin kokemuksiin, joista on paljon kirjoitettu lehdistössä. Tunnetuin vanhusten hoitokoti on Weespin kunnassa lähellä Amsterdamia sijaitseva Hogewey.

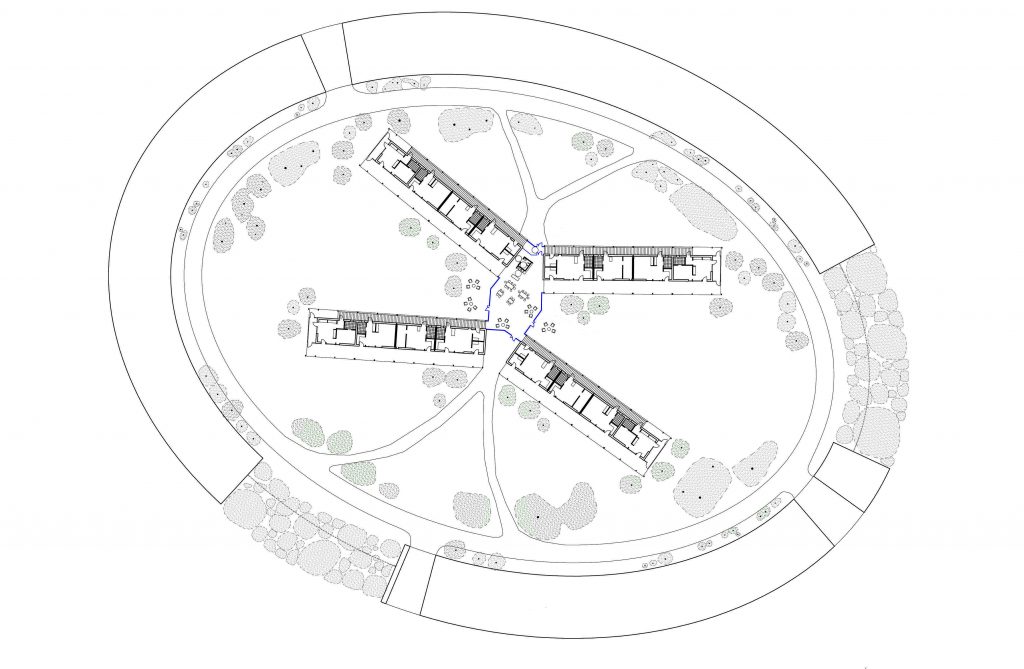

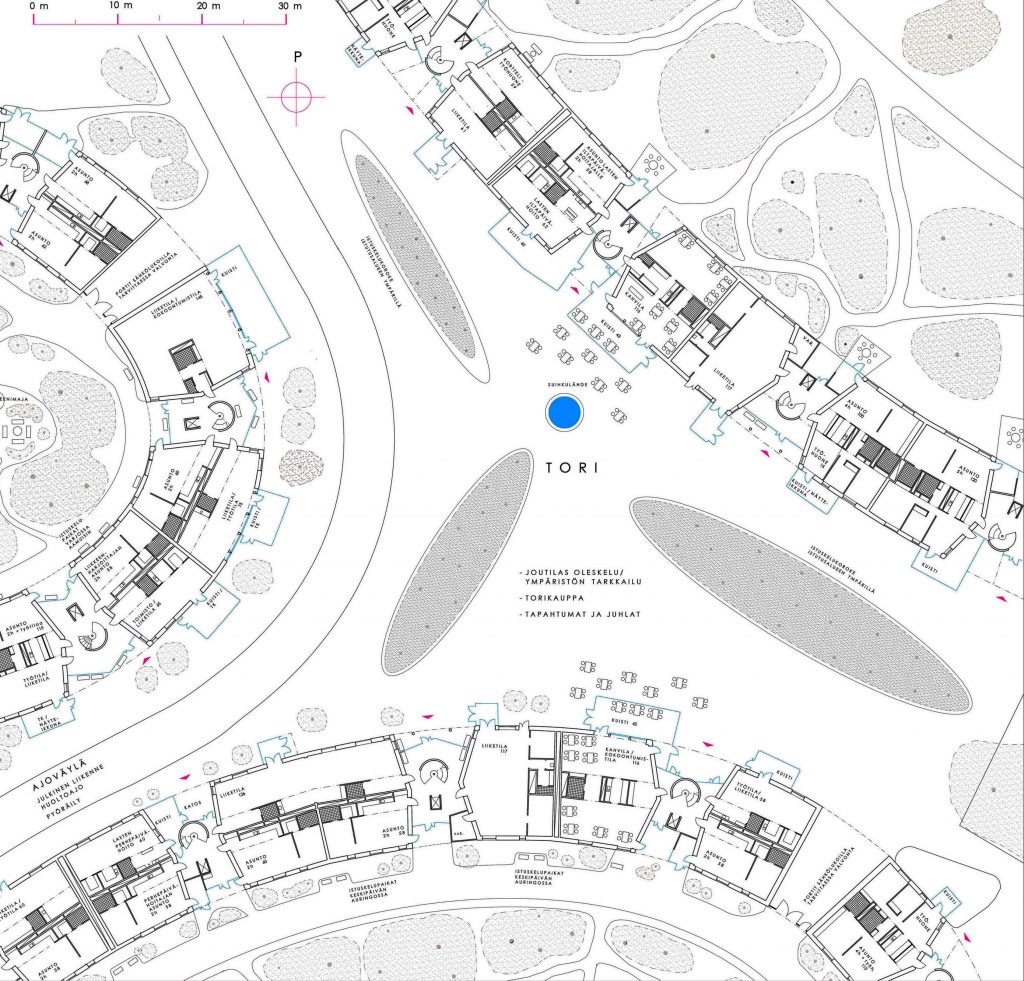

Niemiskylän kortteleissa asuisivat kaiken ikäiset: perheet, lapset, yksin asuvat ja ne muistisairaat, joiden turvallisuus ei vaadi eristämistä.

Ikäryhmiä ei pitäisi eristää toisistaan. Voisiko tulevaisuudessa vanha ihminen kuulua yhteisöön ja naapurusto osaltaan auttaisi pitämään huolta hänestä? Fyysisen esteettömyyden lisäksi ympäristö olisi mentaalisesti esteetön. Joskus oudostikin käyttäytyvä muistisairas ei herättäisi kielteistä huomiota, kun ihmiset tottuisivat siihen, että meitä ihmisiä on monen laisia.

Suljetun, kyllin suuren korttelin sisäpuolella muistisairaan olisi myös turvallista asua. Hoitohenkilökuntaa tarvittaisiin myös kortteleissa, mutta laitospaikkojen määrä saattaisi vähentyä.

Mallia voisi ottaa myös menneisyydestä. Kirjailija Sirpa Kähkönen kuvaa Kuopio -sarjassaan elämää kaupungin puutalokorttelissa 1930 -luvulta lähtien. Toisen maailmansodan vuosina elämä oli niukkaa ja epävarmaa, mutta kukaan ei jäänyt kokonaan yksin, vaikka läheiset eivät palanneet sodasta. Niin orpo lapsi kuin yksin asuva vanhus saivat kokea olevansa osa naapuruston muodostamaa yhteisöä.

During our participation in the Helsinki Vision 2050 competition in 2007, architect Pekka Hänninen brought up an idea: instead of concentrating residential building in the metropolitan area, in the Helsinki peninsula, the building could be targeted to villages with town centres that are easily accessible via train connections.

Niemiskylä could be located beside any medium-sized Finnish city. A convenient train connection to the village would run directly from the city stations. It wouldn’t be necessary to own a car to get around within the village area.

If Niemiskylä was built as an independent settlement, stations would be built for public transport and there would be allocated areas for parking on the outskirts of the village.

The idea of Niemiskylä residential blocks is based on case studies from the Netherlands that have been widely featured in the press. The most known is that of the ‘care village’ Hogewey located in the municipality of Weesp, near Amsterdam.People of all ages would live within the blocks of Niemiskylä: families, children, those living alone and those with memory disorders, who don’t require isolation for their safety.

Different age groups shouldn’t live isolated from one another. Are there ways to form a community where the neighbourhood can act as a support system for the elderly? In addition to ensuring physical accessibility, the environment would also be mentally accessible; any negative attention towards a person with a memory disorder, whose behaviour could on occasion be perceived as strange, could be avoided with familiarity and understanding.

Residing inside a large enough, closed block structure would also be safe for individuals with memory disorders. Nursing staff would be needed in the neighbourhood, but the number of facilities could be reduced.

There are also ways to learn from the past. The book series “Kuopio” depicts life in the 1930s, first in Kuopio and then in a small town in Eastern Finland. The author Sirpa Kähkönen describes living in a block of wooden houses during World War II; life was modest and shadowed by uncertainty, but no one was left alone, even if their loved ones did not return from the war. Both orphaned children and elderly living alone were welcomed as a part of the neighbourhood community.